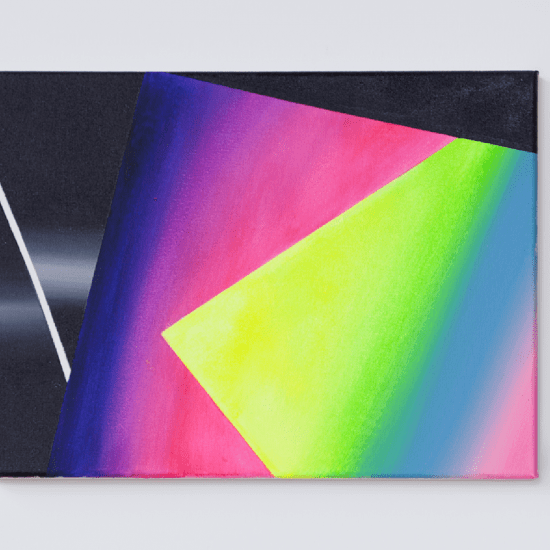

Noise XIX

Acrylic on canvas

60 x 60 cm

2013

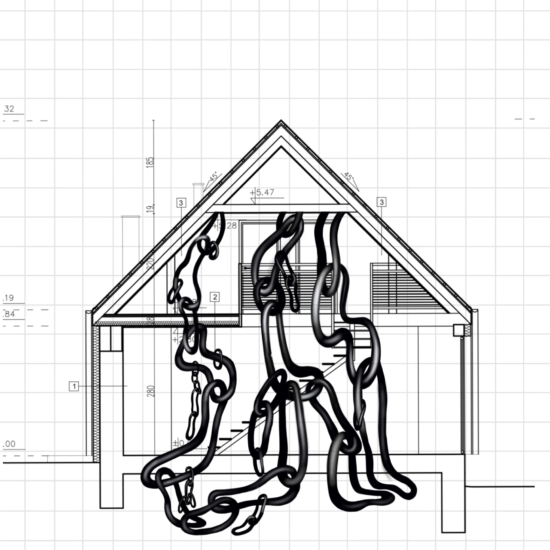

Pictures of skin confront us, as spectators, with our own bodies. The historical study of visual culture of skin raises interesting issues that are less evident in a study of the depiction of nature. The quest for clean skin in sanitary endeavours and soap advertisements pointed to the emergence of both individual responsibility and social control for proper care of the human body. In pursuit of skin cleanliness, then, a morale of cleanliness was attached to the skin demanding internalised self-control of the body. Judgments of outside appearance became related to a clean healthy skin. Pictures of skin consequently affected perceptions of people’s own bodies. What’s more, the urge to protect the privacy of the patient in medical photography at the end of the nineteenth century reaffirms the mirroring of contemporary societal worries and attention to the visual exposure of bodies. Depicting skin was about the presentation and dissemination of knowledge, but even more so about society’s preoccupations with human bodies at that particular time. ²

The skin was a gateway into the body and disease, as well as a canvas of expression and individuality.³

Acrylic painting on canvas painted in Szczecinek, a small historical city in Middle Pomerania, northwestern Poland. A shorthand to represent the city structures and its inner turbulent history. Inspired by Szczecinek’s resident German physician Friedrich Jacob Behrend whose published works among other topics treat about public hygiene. For more info about Behrend, the visual culture in nineteenth-century medicine, and “the incalculable blessings of clean skin,” check out Mieneke te Hennepe’s paper. It’s a bit bewildering but interesting.

Graffiti on city walls stands as a distinctive form of street art, infusing urban spaces with color and vitality. In a parallel vein, the human skin, adorned with tattoos and other forms of body art, serves as a visual representation of individuality and expression. The parallel between cities and the human skin lies in their status as living entities marked by unique histories. Graffiti tells the story of a city’s cultural diversity, mirroring the manner in which changes on the skin narrate an individual’s journey.

¹ Hennepe (2007). Depicting skin: visual culture in nineteenth-century medicine (Doctoral Thesis, Maastricht University). Maastricht University (p. 12, in Jones & Galison, 1999).

² te Hennepe, M. (2007). Depicting skin: visual culture in nineteenth-century medicine (Doctoral Thesis, Maastricht University). Maastricht University. https://doi.org/10.26481/dis.20070920mh

³ Hennepe (2007). Depicting skin: visual culture in nineteenth-century medicine (Doctoral Thesis, Maastricht University). Maastricht University (p.12)